Django for Pork Chops#

About

The Pork Chop pages are intended to help people coming into Cobalt from a bridge background who are not experienced Django developers. They are NOT required reading for Django developers.

This assumes you know Python, if you don’t then you should first read Python for Pork Chops.

Introduction#

It takes about two years to become proficient in Django, some people are quicker and some are slower. This document is intended to try to help people to get there quicker.

As someone wise once said (possibly Eleanor Roosevelt), you should try to learn from other’s mistakes as there isn’t time to make them all yourself. Here are some snippets to get you going.

These are basically things I wish I had known before I got started, although some things won’t make total sense to you to begin with.

First Steps#

If you haven’t used Django before then your best bet is a Youtube video series, a tutorial or a paid course. There are lots to choose from. Be aware that you will never use half of the stuff that they try to teach you. No real Django developer knows the commands to create a project from scratch or to add an application to an existing project, it doesn’t happen often enough for you to need to memorise it and it can be looked up easily. What they do know is that both of these things are possible, and so will you when you finish your training.

There are really only a few key concepts that you need to understand to get started.

I recommend doing something that takes about 6-10 hours, much less will be too superficial and much more is just too long.

Information#

Syntax really doesn’t matter. For example, as long as you remember there is a template tag that formats numbers, you can easily Google it to find out the right word to use. What matters is design and patterns.

The internet is full of opinion pieces on how to do such-and-such in Django. There are also millions of Stack Overflow questions, some of which are useful. The problem is that about 50% of the content is wrong. Some of it is just out of date which is understandable. Often something that needed a work around in version 1.8 has been fixed in 3.2. The answer will still be there though (on Stack Overflow scroll down to the bottom and look for Update, this will often have a less popular answer that is correct for the current version).

Why is so much content wrong? Often the videos and articles are written by people who have never actually written a real Django application. Good Django developers get paid to write code, they don’t have time to make youtube videos about it. For that reason talks at conferences are often much better than articles.

The other problem is that someone who is seen as an influencer says something stupid and all the nodding heads copy it. The best thing is to only ever take what you find on the internet as suggestions and to work out for yourself if they are good suggestions or not. I will go through some of them here. Of course the same advice applies to this document.

Journey#

Let us set some markers for you to track your journey as a Django developer. See how far you have come already and what things might be next.

Level 1 - Basic Explorer#

You can write Django that works. You have got the hang of views and templates. You have probably written three things in three different ways but you are getting there. Some things confuse you and it takes a long time to work things out, but you get there in the end.

Level 2 - Quietly Confident#

You have started to really understand models. You can use foreign keys to get data that you used to have to do in two separate queries. You don’t have to look up the common template tags any more. You have discovered Crispy Forms and spent quite a long time getting them to do what you want. You think you know how static works now but you still aren’t sure which of the static directories is which.

Level 3 - Clunky Builder#

You swear you will never use Crispy Forms again and you build your own HTML forms. You have discovered ‘include’ and ‘extends’ and your templates are looking nicer. You have played with something else really cool, maybe writing your own template tags or overriding save() in models, but you can’t remember where you put it.

Level 4 - Baby Guru#

You found a bunch of Django add-ons including the debug toolbar and it showed how poor some of your database queries are. You now know what an N+1 problem is and you have started getting your head around select_related and prefetch_related. You have finally started writing some tests.

Level 5 - Zen#

You are now a fully initiated Django Master. I don’t know what things you can do at this level as I haven’t got there yet myself, but I bet they are pretty awesome.

Principles#

Django, and Python for that matter, is heavy on principles. You will hear people talking about DRY and being Pythonic, which probably makes you want to reach for a sick bag. Tim Peters came up with 20 aphorisms (yup, maybe get a bucket this time) for Python, called the The Zen of Python (make it is a large bucket). This is even given the honour of being a Python Enhancement Proposal (PEP) and is hidden in the source code as an Easter Egg. I think he was on his second bottle of Midori when he wrote these though as all but one of them are complete nonsense. He also only wrote down 19 presumably beacuse when you finally attain enlightenment as a Python programmer the 20th one will be self evident. Or more likely it was even worse than “Although that way may not be obvious at first unless you’re Dutch.”.

Django nerds also like to talk about DRY (Don’t Repeat Yourself) as if it was something new. You’ll work this out entirely on your own after you have to update very similar code in four different places and decide to create a common function for it.

Useful Ones#

Okay, so which principles are actually useful here.

Do What Django Wants#

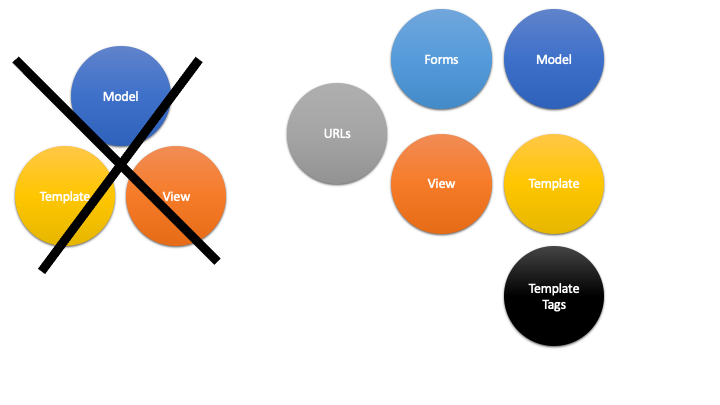

You are using the Django framework so do things the Django way even if you don’t like it. Consistency is much more important than anything else when maintaining code so if you stick to how Django was designed you won’t go far wrong. Django says - Database stuff goes in Models, Business logic goes in Views, Validation goes in Forms and Presentation stuff goes in Templates. If you find yourself writing presentation stuff in a form (I’m looking at you Crispy Forms) then you are making a mistake.

Explicit is Better than Implicit#

This is the one that Tim Peters got right. All it means is don’t hide stuff that will be hard for others to find. For example, when you start writing your own template tags and using them everywhere, you will be tempted to add them to context_processors instead of having to load them in every template. Now you find the exception where you don’t want to load it in a template. Maybe there is a name clash with another set of template tags that you want to use. Good luck finding how it got loaded. Your code won’t run any faster for loading the template tags in a different place (slower for all of the times you don’t use them).

You could always put a comment at the top of your templates to tell the poor person who comes along to support it that this template uses template tags from my_tags. The clever people who brought you Django actually have a shorthand notation for this comment:

{% load my_tags %}

Signals are another good way to obscure your code. So is overriding methods unless you use them in a lot of places. Here is a simple example. You have a model with a CharField defined that has a max_length of 20. You hit a problem when something longer than 20 gets put into the field. You could make it bigger or change it to a TextField (infinite length but same properties) but you aren’t sure of the consequences so instead you do this:

my_thing.short_field = random_value[:20]

my_thing.save()

Now it works fine. But what if this happens somewhere else? You could look for all instances of random_value and do this to them all, but that is ugly and someone else might add a new one and forget to do it. What about just overriding the save() method on the model for my_thing? Now you are only making the change in one place and your code is far simpler:

my_thing.short_field = random_value

my_thing.save()

def save():

self.short_field = self.short_field[:20]

Nice solution! Except six months later you are trying to work out why data in short_field is getting truncated. The system throws no errors and the code looks fine. When you examine the variables they have the long value but later it has been truncated. This could take you a very long time to solve.

Tim Peters has two others that are pretty much okay, he actually split one thing into two in his late night effort to get to 20: “Errors should never pass silently.” and “Unless explicitly silenced.”. That is pretty much the same thing as here though, nice try Tim.

Write Comments#

There are a bunch of dangerous idiots going around preaching that comments are the work of the devil and finding comments in code is a sure sign that the code is bad, otherwise why would you need to write comments? Use better variable names, refactor the code to be easier to read, delete the comments. These people are insane, ignore them. Here is a much better philosophy - instead of thinking that the comments are there to explain the code to humans, try thinking that the code is only there because the computer can’t read the comments.

Apart from showing your most beautiful work to people at parties there are only three reasons to be looking at code:

It’s broken and you need to fix it

It works but you need it to do something else now

You want to understand what it does and how (to copy it or to use it)

Every one of these is going to be easier if the code has comments, especially the first one which is the worst reason to be looking at code (second worst, you could be at a party and someone is showing it to you).

Take this example:

# Save original value

original_value = request.POST.get("my_value")

# Loop through and create list of options

for item in items:

my_list.append(item)

# add the original value back into our list

my_list.append(item)

It is very obvious that the last line of code doesn’t do what its comment says it is going to do.

There are lots of excuses for writing bad code (short of time, hate my job, drunk, stupid) but no excuse for not writing comments.

Tools#

IDE#

Choose a good IDE and learn the half a dozen shortcut commands that you will use all the time. PyCharm is really worth the money.

PyCharm shortcuts (Mac):

CMD-/Comment out lineCMD-DDuplicateCMD-DownArrowGo to code (click on a function name first)CMD+OPT-BackArrowGo backOPT-MouseClickDuplicate cursor (I thought I’d never use this, but I use it all the time)

You will write code with bugs in it, and it will be found. The default location for finding bugs is production, but with appropriate testing you can catch them earlier. The best place to catch them is in your IDE. PyCharm is pretty good at this so look out for highlighted errors.

Virtual Environments#

These are a no-brainer really. Virtualenv and pip are a perfect combination, or use something similar if you prefer, it is the idea of keeping things isolated that really matters.

Pre-Commits#

Set up your git (or similar) environment with pre-commits so they can save you from yourself.

- Black

An opinionated code formatter. Essential.

- Flake8

A middle of the road linter. “What! There is nothing wrong with that, stupid Flake8! Oh… hang on, I think it might be right.”

- Djhtml

Black only formats Python, this does HTML for you. It understands Django so won’t break things like some other HTML formatter have a habit of doing.

Refactoring#

This has nothing really to do with Django but neither did the last point about comments and you didn’t notice until I just pointed it out.

Refactoring is the most fun you can have in programming without being able to tell anyone you did it. Ignoring the obvious parallels, there is nothing better than taking some badly structured code and turning it into something beautiful and easy to maintain.

In the examples above, we had views.py and a templates folder. Once things get big, you will need to split them. You can make views a directory and have a bunch of separate files in there that map to logically different parts of your system. If things get even bigger then you can make those things directories too instead of files:

myapp

\-views

\-players

common.py

basic.py

advance.py

\-conveners

global.py

state.py

You should try to keep your views reasonably short (Cobalt doesn’t do this nearly well enough at the moment and needs to be refactored). You can move logic out of the function and into somewhere else, either other functions in the same file or in other files or even classes if that works better. You will hear people saying “Fat Models, Thin Views”, ignore them. That is totally stupid. Yes, keep your views thin, but move the business logic into other parts of the view structure, not into your models. Models should only have things that relate directly to data. Ultimately Django is just Python code so you can move your code wherever you like. If you come across someone who says the business logic should go into the model, tell them you think that is wrong, the latest thinking is that it should go into settings.py.

Hint

In Python abc.views.fishcake could be either a function inside views.py or a file in the directory views. When refactoring, you will confuse your IDE if you have both views.py and views the directory at the same time. It is better to create a directory called something else and rename it to views once you have moved everything across and can delete views.py.

Things to Avoid#

Lots of people will disagree with me, but I would avoid the following:

- Crispy Forms

This is a presentation tool that makes you write code in a Form. That is just wrong. I have used it a lot and I wish I hadn’t.

- Class Based Views

Function Based Views (FBVs) were the first thing that Django came with and do everything you need. They are easy to follow. Class Based Views (CBVs) came later as a way to hide bits of your code in lots of different places to make it harder to look after. There is a tendency to think that Class=Good, Function=Bad but that is not the case. CBVs come with a bunch of basic things to use as templates, however in the real world they never do exactly what you want and you will need to extend serialisers and generally muck about with them. Stick with FBVs, they are fine.

- Celery

Its too complicated for most use cases. Cron and Django management commands work fine.

- Makemigrations in Production

Migrations are part of your source code. Run

manage.py makemigrationsin development and save the migration files as part of your code base. Runmanage.py migratein production to apply the migrations.- Signals

Another way to hide your code up a chimney so the police won’t find it if you get raided (but nor will you).

- Save Methods

Sometimes you can’t avoid doing things in the save method of a model (e.g. using bleach to see if the code is safe). If you can avoid it though, do. Remember, explicit it better than implicit.

- Docker

Docker is fine for large environments were you cannot control the run time environment properly, or for development environments with a lot of developers. For most Django implementations you can get by with

pipandvirtualenvjust fine. Less complexity, less runtime overhead.

Things I used to do but promise never to do again#

Here are some things to watch out for. They are not necessarily all terrible, but people will think more of you as a developer if you can avoid them.

Using Strings instead of Constants#

There is a lot of Cobalt code that still has this problem. Fix it as you find it.

Don’t do this:

model.py

CHOICES = [("Active", "Active"), ("Inactive", "Inactive")]

class MyThing(models.Model):

status = models.CharField(choices=CHOICES, max_length=400, default="Inactive")

views.py

if thing.status == "Active":

# Do something

It will work fine, but this is better:

model.py

class MyThing(models.Model):

class SpecificStatus(models.TextChoices):

ACTIVE = 'AC', 'Active'

INACTIVE = 'IN', 'Inactive'

# This works too - the readable name is taken from the variable name

ACTIVE = 'AC'

INACTIVE = 'IN'

specific_status = models.CharField(choices=SpecificStatus.choices, max_length=2, default=SpecificStatus.ACTIVE)

views.py

if thing.specific_status == SpecificStatus.ACTIVE:

# Do something

This not only lets you change the readable name (and only specify it in one place) but more importantly you will get an error if you type the variable name wrongly and your IDE will autocomplete it for you.

Turn Away Unwanted Guests at the Front Door#

Don’t do this:

if state = EXPECTED_STATE:

# Do a bunch of things

elif state == BAD_STATE:

return "Error - bad state"

else:

return "Error - unexpected state"

Do this instead:

if state == BAD_STATE:

return "Error - bad state"

if state != EXPECTED_STATE:

return "Error - unexpected state"

# Now do your stuff, but one indentation further out and code is easier to read

Use Custom Exceptions#

Exceptions are the acceptable face of the old GOTO statement. They let you quit your code in the middle if something goes wrong. However, it is better to say exactly what went wrong and not just use a built in exception.

Don’t do this:

raise ValueError

Do this:

class CSVInconsistentDataException(Exception):

def __init__(self, filename, message):

self.message = message

self.filename = filename

def __str__(self):

return self.message

raise CSVInconsistentDataException(filename, "Bad data found on row 7 - date field missing from column 8")

Functions should conduct the orchestra or play one instrument well#

If you have a function that takes a parameter to tell it what to do, then either replace it with specific functions or have it call specific functions. Don’t have a function that tries to play the flute and the violin at the same time.

But… this:

def my_func(age):

if age < 5:

log_it("Under 5 found")

return "This person is under 5 years old"

# do something

Is better than this:

def my_func(age):

if age < 5:

return _handle_under_5()

# do something

def _handle_under_5():

log_it("Under 5 found")

return "This person is under 5 years old"